The State of Reshoring U.S. Manufacturing Jobs

Over the long term, manufacturing companies are repatriating back to the U.S. In the short term, an economic trade war has led to some uncertainty.

Over the long term, manufacturing companies are repatriating back to the U.S. In the short term, an economic trade war has led to some uncertainty.

In the wake of a trade war and tariffs, what’s going on with reshoring manufacturing jobs in the U.S.? We talk to the guru of reshoring, Harry Moser, of the Reshoring Initiative.

After decades of watching many companies move their manufacturing out of the U.S., Harry Moser founded the Reshoring Initiative. The Reshoring Initiative supports the repatriation of manufacturing in the U.S. and offers both free and paid tools that help companies better understand that lower wages do not necessarily lower the total cost of ownership.

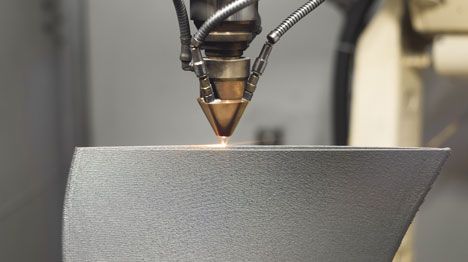

Moser is a former president of machine tool maker GF AgieCharmilles (which is today known as GF Machining Solutions), so he is well-versed in the economic impact on machining, tooling and metalworking. We recently caught up with Moser for a conversation on the state of reshoring, the impact of the trade war and tariffs—and how the U.S. can better compete in trade and manufacturing overall.

We last spoke in 2016. What’s been the trajectory of reshoring, by the numbers?

MOSER: To give you a little perspective: 2017 had 171,000 manufacturing jobs announced coming back to the U.S., which was 50 percent above 2016’s numbers—and 2,800 percent above 2010. So the rate of jobs coming back is up dramatically and is a significant number now. The numbers include reshoring and “FDI,” or “foreign direct investment,” such as companies like Toyota. That 171,000 number is important because it equals about 83 percent of the total increase in manufacturing jobs in 2017. The caveat is that the jobs are announced in 2017, but it takes a couple of years for them to be filled: They build a factory, they bring in equipment, hire people, etc. To look at it without that lag effect, you look at a longer term. So if you look from 2010 to 2017 you see that reshoring and FDI account for about 3 percent of total manufacturing employment and about 40 percent of the increase in manufacturing employment over those years. It makes a real difference and has done well overall.

And what’s the status of reshoring for the most recent year that there is data (2018)?

MOSER: Well, 2017 was a peak year. For 2018, the numbers are projected to be about 131,000 jobs from reshoring and FDI. It’s down roughly 24 percent from last year. But it’s up 13 percent from the previous high in 2016 (which was roughly 113,000)—and it’s up 82 percent from the 2010 to 2017 average. So it’s not a new record, but it’s still the second highest year after 2017.

Why the fluctuation between 2017 and 2018?

MOSER: We’d say the slowdown occurred due to a combination of factors including the dysfunction in Washington, the trade dispute and the dollar rising during the year. People see the (dollar) number going up and up. The Europeans are not raising their interest rates. We are. The Fed’s adamant about raising the rates. That means investment in the U.S. isn’t going to be as strong. The U.S. is going to be even less competitive. Therefore, why would you want to bring jobs back to the U.S.? I’d say the political factors were as big an issue as anything.

How are tariffs affecting reshoring today?

MOSER: There’s a group called Coalition for a Prosperous America and another one, Alliance for American Manufacturing, and they both put out some numbers on how many jobs have been brought back by the steel and aluminum tariffs and they get into the 11,000 range. And that’s great. However, I don’t think any group has done a great job of tracking how many jobs were lost at the machine shop or the stamping shop because the price of steel went up and they lost the business to Mexico or China because the Chinese stamped parts are not tariffed but the Chinese steel is … So we think at best, the steel and aluminum tariffs were neutral to net negative … The Chinese tariffs are a mixed bag. For some U.S. companies, their components are more expensive. And so they may move the assembly to another country, say Mexico or Vietnam, to avoid tariffs, then ship assembled parts to the U.S.

From a transactional viewpoint, I think tariffs from China are neutral. Though I do think they create uncertainty—and business abhors uncertainty, so I’m sure some companies have put off their decisions to invest here until they see what’s going to happen, especially if they export. Because you could wind up with huge Chinese tariffs on the things you want to export. But in the long run, I think they are focusing on the right problem: China represents 30 percent of our goods trade deficit—and they ship three or four times what we ship them, so it’s totally out of balance.

But it’s not the only problem when it comes to today’s manufacturing, is it?

MOSER: Is it China’s fault? Partially. There is the favoring of their own companies, the currency manipulation and the intellectual property theft issues and corruption that are widely reported. It certainly hurts us. But we say that the biggest problems related to trade and the economy are self-imposed. We do not have the skilled workforce we need. We allow ourselves to be the reserve currency and the safe haven, which forces up the value of the dollar so that we’re not competitive. We don’t have a “VAT”—a value-added tax, and almost every other country does. China, for example, in addition to a higher import tax, also has a 15 percent value-added tax on U.S. goods, which is not really mentioned almost at all.

Shifting gears a little, what’s the role of automation in total cost of ownership from a trade competitiveness standpoint?

MOSER: Automation can help make up for the lack of people. China is spending three to four times more on automation than we are—especially in CNC machine tools. According to data from the Association for Manufacturing Technology, the U.S. consumed $8 billion in machine tools—and China is in the plus-$30 million range. And the consumption of robotics in China is multiples higher than us—in a country where the wage rates are only 20 percent of our rates. They are increasing robotics and paying workers $4 an hour—and the U.S. is not competing at the same level and paying $20 an hour [an average]. The effect is that it helps increase their productivity faster and it covers up some of that increase in the wage rate. It keeps them more competitive. It allows them to not have to raise their prices on goods and ameliorates wage rates.

But to clarify, China has a skills gap issue; it too doesn’t have enough workers. They’ve done a good job shifting workers from the western rural farms to the industrial eastern cities, but they’re running out of people to shift, therefore the need and push for more and more robotics use. But we need it too. You read the articles about 600,000 manufacturing job openings. We’re not bad, but we don’t invest enough. Look at Germany, with half the population, invests more than we do in manufacturing. Korea invests a lot more in robotics than we do.

Does the U.S. government invest enough in manufacturing today?

MOSER: No. We don’t invest enough in people. We don’t invest enough in the equipment, buildings, training or in lean [manufacturing] … To me, it’s the question of when do companies invest? Companies invest when they are operating at 80 percent or higher of capacity and utilization—and business is growing and is profitable, which is happening now. So the way to get investment in people and things is to get to those utilization levels—and to get the price of the dollar down and use a value-added tax. But you need the skilled workforce and you need companies to be busy.

Can you do this without the dollar’s price going down and VAT alone?

MOSER: Well, look at Germany. Its wage rates are on par with the U.S., but it has a trade surplus that is 5 percent of its GDP. We have a trade deficit of 3 percent of GDP. Why is that? It has a skilled workforce. It has technical institutes. It has a cultural propensity for manufacturing and trade work being valued. And they are the big, strong economic power in Europe with a lot of weaker countries around them to sell to. How long would it take us to get there? Decades and decades. … The U.S. is not competitive. Seventy percent of the decision on where companies buy product is based on price. On average, the U.S. is roughly 40 percent higher on prices compared to China. Of our 10 biggest trading partners, we have trade deficits with nine of them with a minor trade surplus with the U.K.

What’s your message to metalworkers and machinists facing ever-increasing automated manufacturing environments?

MOSER: To the individual, it’s the same thing they’ve been told all their life: Keep getting new skills and be competitive on the new processes … From a societal viewpoint, and whether the robots will take all of our jobs, I believe the following: We will lose more jobs to Chinese automation if we do not automate ourselves than we will to U.S. automation if we do.

Do you have anything new going on to help spark reshoring in the U.S.?

MOSER: Our main offering, as you know, is the TCO Estimator, where companies can plug in their own information and perform the math for themselves on the total cost of ownership. Companies generally find that 15 to 20 percent of what’s offshore should come back to the U.S. We now also offer a paid Import Substitution Program. Companies tell us what they make—whether valve fittings or axles, what have you, and we allow them to see who the biggest importers are, where they are, how much they are importing—and then we train companies to use the TCO tool to help convince those importers to buy from them instead of continuing to import.