Overcome the Ongoing Challenges of Long-Reach Machining

In general, solid fixturing, rigid tooling and careful tool application make up the basic foundation for accurate, productive boring and long-reach turning processes.

In general, solid fixturing, rigid tooling and careful tool application make up the basic foundation for accurate, productive boring and long-reach turning processes.

A number of current trends in manufacturing are magnifying the difficulty of creating precision bores and performing turning operations with extended-length tools. Demand for tighter tolerances and unfailing repeatability grows continuously. New high-performance workpiece materials are more difficult to machine, boosting stress within the machining system. To save time and money, manufacturers are consolidating multiple parts into single monolithic workpieces that require machining of deep bores and turning of complex components on multitasking machine tools.

Manufacturers seeking to overcome these challenges must study all elements of their machining systems and apply techniques and tools that will assure success. Among the key elements are machine stability, tool holding, workpiece clamping and cutting tool geometry. In general, solid fixturing, rigid tooling and careful tool application make up the basic foundation for accurate, productive boring and long-reach turning processes.

Producers of oil and gas, power generation and aerospace components are prime candidates for updated tooling and techniques because they regularly deal with large, complex parts with features that require the use of extended-length tools. Many of the parts are made from tough alloys that are difficult to machine and thereby produce high, vibration-generating cutting forces. In general, nearly any manufacturer can benefit from improving productivity and reducing costs in long-reach boring operations.

DEFLECTION AND VIBRATION

Deep boring is distinguished from other cutting operations in that the cutting edge operates in the bore at an extended distance from the connection to the machine. Long-reach internal turning operations feature similar conditions, and both these boring and turning operations can involve holes with interrupted cuts, as is the case on workpieces like pump or compressor housings. The amount of resulting tool overhang is dictated by the depth of the hole and can result in deflection of the boring bar or extended-length turning tool.

Deflection magnifies the changing forces in a cutting process and can cause vibration and chatter that degrade part surface quality, quickly wear or break cutting tools and damage machine tool components, such as spindles, and cause the need for expensive repairs and long periods of downtime. The varying forces result from machine component imbalances, lack of system rigidity or sympathetic vibration of elements of the machining system. Cutting pressures also change as the tool is periodically loaded and unloaded while chips form and break. Negative effects of machining vibrations include poor surface finish, inaccurate bore dimensions, rapid tool wear, reduced material rates, increased production cost and damage to tool holders and machine tools.

MACHINE RIGIDITY AND WORKPIECE FIXTURING

The basic approach to controlling vibration in machining operations involves maximizing the rigidity of the elements of the machining system. To restrict unwanted movement, a machine tool should be built with rigid, heavy structural elements reinforced with concrete or other vibration-absorbing material. Machine bearings and bushings must be tight and solid.

Workpieces must be accurately located and securely held within the machine tool. Fixtures should be designed with simplicity and rigidity as primary concerns, and clamps should be located as close as possible to the cutting operations. From a workpiece perspective, thin-walled parts or welded parts and those with unsupported sections are prone to vibration when machined. Parts can be redesigned to improve rigidity, but such design changes can add weight and compromise performance of the machined product.

TOOLHOLDING

To maximize rigidity, a boring bar or turning bar must be as short as possible but remain long enough to machine the entire length of the bore or component. Boring bar diameter should be the largest possible that will fit the bore and still permit efficient evacuation of cut chips.

As chips form and break, cutting forces rise and fall. The variations in force become an additional source of vibration that may interact in sympathy with the tool holder’s or machine’s natural mode of vibration and become self-sustaining or even increase. Other sources of such vibrations include worn tools or those not taking a deep enough pass. These cause process instability, or resonance that also synchronize with the natural frequency of a machine’s spindle or the tool to then generate unwanted vibrations.

A long boring bar or turning bar overhang can trigger vibration in a machining system. The basic approach to vibration control includes the use of short, rigid tools. The larger the ratio of bar length to diameter, the greater the chance that vibration will occur.

Different bar materials provide different vibration behavior. Steel bars generally are vibration resistant up to a 4:1 length to diameter of bar (L/D) ratio. Heavy metal bars made from tungsten alloys are denser than steel and can handle L/D of bar ratios in the range of 6:1. Solid carbide bars provide higher rigidity and permit up to L/D of bar ratios of 8:1, along with the possible disadvantage of higher cost, especially where a large-diameter bar is required.

An alternative way to damp vibrations involves a tunable bar. The bar features an internal mass damper that is designed to resonate out of phase with the unwanted vibration, absorb its energy and minimize the vibratory motion. The Steadyline® system from Seco Tools (see sidebar), for example, features a pre-tuned vibration damper consisting of a damper mass made of high-density material suspended inside the toolholder bar via radial absorbing elements. The damper mass absorbs vibration immediately when it is transmitted by the cutting tool to the body of the bar.

More complex and expensive active tooling vibration control can take the form of electronically activated devices that sense the existence of vibration and use electronic actuators to produce secondary motion in the toolholder to cancel the unwanted movement.

WORKPIECE MATERIAL

The cutting characteristics of the workpiece material may contribute to the generation of vibration. The hardness of the material, a tendency to built-up edge or work hardening, or the presence of hard inclusions alter or interrupt cutting forces and may generate vibrations. To some degree, adjusting cutting parameters can minimize vibrations when machining certain materials.

CUTTING TOOL GEOMETRY

The cutting tool itself is subject to tangential and radial deflection. Radial deflection affects the accuracy of the bore diameter. In tangential deflection the insert is forced downward away from the part centerline. Especially when boring small diameter holes, the curving internal diameter of the hole reduces the clearance angle between the insert and the bore.

Tangential deflection will push the tool downward and away from the centerline of the component being machined, reducing the clearance angle. Radial deflection reduces cutting depth, affecting machining accuracy and altering chip thickness. The changes in depth of cut alter cutting forces and can result in vibration.

Insert geometry features including rake, lead angle and nose radius can either magnify or damp vibration. Positive rake inserts, for instance, create less tangential cutting force. But the positive rake angle configuration can reduce clearance, which can lead to rubbing and vibration. A large rake angle and small edge angle produce a sharp cutting edge, which reduces cutting forces. However, the sharp edge may be subject to impact damage or uneven wear, which will affect surface finish of the bore.

A small cutting edge lead angle produces larger axial cutting forces, while a large lead angle produces force in the radial direction. Axial forces have limited effect on boring operations, so a small lead angle can be desirable. But a small lead angle also concentrates cutting forces on a smaller section of the cutting edge than a large lead angle, with possible negative effect on tool life. In addition, a tool’s lead angle affects chip thickness and the direction of chip flow.

Insert nose radius should be smaller than the cutting depth to minimize radial cutting forces.

CHIP CONTROL

Clearing the cut chips from the bore is a key issue in boring operations. Insert geometry, cutting speeds and workpiece material cutting characteristics all influence chip control. Short chips are desirable in boring because they are easier to evacuate from the bore and minimize forces on the cutting edge. But the highly contoured insert geometries designed to break chips tend to consume more power and may cause vibration.

Operations intended to create a good surface finish may require a light depth of cut that will produce thinner chips that magnify the chip control problem. Increasing feed rate may break chips but can increase cutting forces and generate chatter, which can negatively affect surface finishes. Higher feed rates can also cause built-up edges when machining low carbon steels, so higher cutting feed rates along with optimum internal coolant supply may be a chip control solution when boring these more malleable steel alloys.

CONCLUSION

Deep hole boring and turning with extended length tools are common and essential metal-cutting operations. Carrying out these processes efficiently requires evaluation of the machining system as a whole to assure that the multiple factors involved in minimizing vibration and assuring product quality are working together to achieve maximum productivity and profitability.

Previously Featured on SECO's News site.

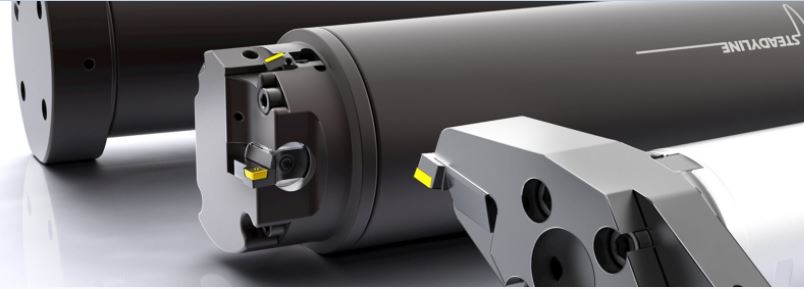

Steadyline® tooling from Seco Tools can enable typical long-overhang operations to be performed twice as fast as with non-damped tools while enhancing part surface finish, extending tool life and reducing stress on the machine tool. The system’s passive/dynamic vibration damping technology makes it possible to accomplish certain applications, such as use of tools with L/D ratios greater than 6:1 that would not otherwise be possible even at minimal machining parameters. Turning and boring operations to depths up to 10xD in small and large holes can be reliable and productive.

The Steadyline® dynamic/passive vibration control system functions on the basis of an interaction of vibration forces. In operation, a cutting force induces motion (vibration) in the holder. To counter vibration, the Steadyline® system employs the properties of an internal second mass engineered to possess the same natural frequency as the external envelope of the bar. The mass is designed to resonate out of phase with the unwanted vibration, absorb its energy and minimize the unwanted motion.

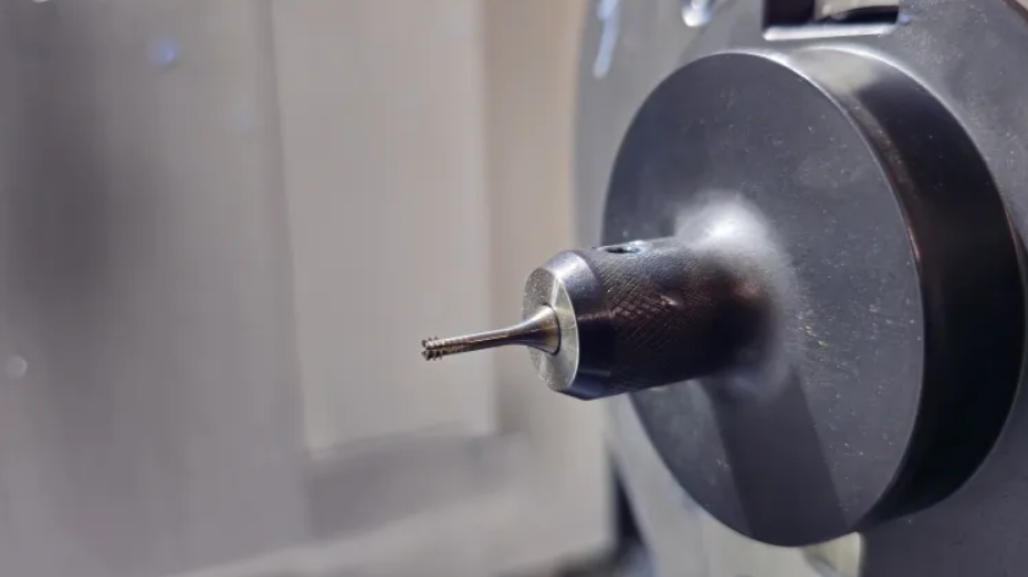

In the Steadyline® system, the vibration-absorbing mass is positioned at the front of the bar where the potential for deflection is highest, and the mass can damp vibration immediately as it is transmitted from the cutting edge to the body of the bar. The Steadyline® system also includes short, compact Seco GL cutting tool heads that place the cutting edge close to the damping mass to maximize the vibration-absorption effect. The system is adaptable to a wide range of applications and is most useful in rough and fine boring as well as contouring, pocketing and slotting.

Seco Tools has expanded its long-reach turning and boring solutions with additions to its series of Steadyline® vibration-damping turning/boring bars and cutting heads. The latest additions include 1.00" (25 mm) and 4.00" (100 mm) diameter Steadyline® bars, GL25 turning heads and a range of BA boring heads for roughing and finishing operations up to diameters of 115 mm.

Boring and turning tool heads can be exchanged quickly using the GL connection, which provides centering accuracy and repeatability of 5 microns and 180° head orientation capability.

The 1.00" (25 mm) diameter bars with GL25 workpiece-side connection include carbide-reinforced bars for the deepest tool overhang challenges up to 250 mm, along with Seco-CaptoÔ, HSK-T/A and cylindrical shank machine-side interfaces. Larger 4.00" (100 mm) diameter bars accommodate existing GL50 turning heads and incorporate Jetstream ToolingÒ high-pressure coolant technology through BA-to-GL50 adapters.

Where conventional tooling options fail, Steadyline® delivers accuracy and confidence in long overhang operations, reducing spindle stress, increasing metal-removal rates, creating smooth surface finishes and extending tool life.

Seco Tools is your complete metalworking solutions provider offering cutting-edge, precision tools for indexable milling, solid milling, hole making, turning, threading, grooving and more. We’re proud to make for makers, invent for inventors, and partner with pioneers. In short - if the right tool for the job exists, we’ll deliver it. If it doesn’t, we’ll create it.